In a funny twist of lingering history, the

FIM book of Motorcycle Land Speed Records notes that on 6th November, 1930, Joseph S. Wright took his

Temple-O.E.C. (Osborne Engineering Company) with supercharged JAP 994cc engine to 150.7 mph down the rod-straight concrete pavé at Cork, Ireland. The 1930 record was a significant advance on the

Ernst Henne/BMW record of 137.58mph, achieved only weeks prior at Ingolstadt, Germany, on a supercharged 750cc ohv machine. But in this case, the history books are all wrong.

150 MILES AN HOUR ON A MOTORCYCLE!

(Click on the image above to see the film from the Record attempt)The O.E.C. was an unusual motorcycle, using

'duplex' steering; an OEC trademark, although not all of their bikes used this system. The advantages of this arcane steering system on these early motorcycles was great stability at speed, plus the possibility of front wheel suspension which didn't alter the steering geometry when compressed by bumps, giving totally 'neutral' steering under all conditions. In practical use, the OEC chassis was reported to be very stable indeed, although resistant to steering input! So, while potholes and broken surfaces brought no front wheel deflection, neither did a hard push on the handlebars...perfect for a speed record chassis actually.

A pair of machines was present at Cork that day; the OEC which had been prepared by veteran speed tuner

Claude Temple, and a 'reserve' machine in case it all went pear-shaped. The second-string machine was a supercharged

Zenith-JAP, of similar engine configuration to the OEC, but in a mid-1920s

Zenith '8/45' racing chassis. Zenith at that date was technically out of business, so no valuable publicity could be gained for the factory from a record run, nor bonuses paid, nor salaries for any helpful staff who built/maintained the machine. While Zenith would be rescued from the trashbin of the Depression in a few months, and carry on making motorcycles until 1948 in fact, the reorganized company, with its star-making

General Manager Freddie Barnes, never sponsored another racer at

Brooklands or built more of their illustrious special 'one off' singles and v-twins, which did so well at speed events around the world - from England to

Argentina!

Joe Wright had already taken the Motorcycle Land Speed Record with the OEC, back on August 31st at Arpajon, France, at 137.32mph

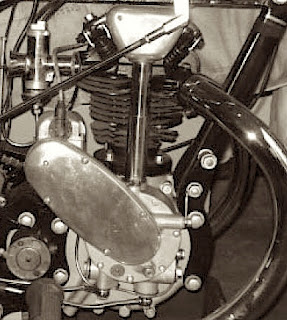

(see top photo with news story), but Henne and his BMW had the cheek to snatch the Record by a mere .3mph, on Septermber 20th. That November day was unlucky for Wright and the team, as the Woodruff key which fixed the crankshaft sprocket sheared off, and the OEC was unable to complete the required two-direction timed runs to take the Record. As you can see in the photo below, the engine mainshaft drove the supercharger as well as the primary chain/gearbox, and was a one-off for which there was presumably no replacement, with probably no time for repair in any case.

Supercharging a v-twin motorcycle is a difficult business, as the compressor blows fuel/air mix at a constant rate into a shared inlet manifold for both cylinders, but as the cylinders aren't evenly spaced physically (as they are on a BMW, for instance), one cylinder inevitably gets a much bigger 'puff' of built-up pressure. Figuring out how to accommodate a different charge for each cylinder led to all sorts of compromises, from restricting the inlet port of one cylinder, to the use of different camshafts/compression ratios/valve sizes for each cylinder, in an effort to keep one cylinder from doing all the 'work' and overheating. It was an imperfect science, as supercharging was still relatively new to motorcycles, and only a handful of blown motorcycles were truly 'sorted out' for racing or record-breaking before WW2. Typically, these had

flat-twin or

four-cylinder engines, with even intake pulses! (Although, of course

Moto Guzzi, typical of their genius at the time, had a lovely

250cc ohc blown single-cylinder which worked a treat).

With the OEC out of action, and

FIM timekeepers being paid by the day, as well as the complicated arrangements with the city of Cork to close their road (and presumably police the area), a World Speed Record was an expensive proposition, and the luxury of a 'second machine'

(above) was in fact very practical...although this may be the only instance in which the second machine was of a completely different make. Imagine

Ernst Henne bringing a

supercharged DKW as a backup for his BMW; simply unthinkable!

But, such was the English motorcycle industry at the time; several very small factories (

Brough Superior, Zenith) competed on friendly terms for national prestige the in record books, while the largest makes (BSA, Triumph, Ariel), nearly ignored top-tier speed competitions such as the Grands Prix and Land Speed Records.

In the event, Wright did indeed set a new Motorcycle Land Speed Record with his trusty Zenith

(above, setting the record, quite clearly on a different machine than the OEC below) at 150.7mph, although the press photographs and film crews of the time were solely focused on the magnificent but ill-fated OEC, as Zenith was out of business and OEC paying the bills. Scandalously, all present played along with the misdirection that the OEC had been the machine burning up the timing strips, and the Zenith was quickly hidden away from history, a situation which still exists in the FIM record books!

Photographs from the actual event show the Zenith lurking in the background

(above), while Joe Wright poses on the OEC, preparing himself for a blast of 150mph wind by taping his leather gloves to his hard-knit woolen sweater, and wrapping more tape around his turtleneck and ankles to stop the wind stretching them, and dragging down his top speed. His custom-made teardrop aluminum helmet is well-documented, but the protective abilities of his wool trousers and sweater at such a speed are dubious at best...but there were no safety requirements in those days, you risked your neck and that was that. Nowadays, when any young squiddie can hit 150mph exactly 8 seconds after parting with cash for a new motorcycle, Wright's efforts might seem quaint, but he was exploring the outer boundaries of motorcycling at the time, and was a brave man indeed.

The record-breaking Joe Wright Zenith was a rumor for decades, becoming a documented story only in the 1980s via the classic motorcycling rags, the whereabouts or existence of the Actual machine known only to very few. I've had the great pleasure of making the Zenith's acquaintance, it does still exist, and is currently undergoing restoration, to be revealed when the time is ripe.

As the OEC also still exists and is in beautiful restored condition, a meeting of the two machines is almost a certainty, at the right event. If motorcycles could talk, I bet the Zenith would have something to say to the OEC...

3:00 AM

3:00 AM