[Mitchell Barnes of Australia is an expert on Blackburne and Excelsior 'Manxman' history, and sends along this story of an O.E.C. racing chassis he found, which he built to replicate a long-lost Isle of Man TT racer from that unusual marque - pd'o]

"It was a red-letter day for small motorcycle manufacturers when Rudge's Depression-era financial woes forced them to wholesale ‘loose’ engines and gearboxes. Ironically, this move helped boost the Rudge name, as a great number of formerly mundane machines suddenly scorched around England and the Continent, Rudge ‘Python’ powered – 250cc to 500cc, the bigger engines with Rudge’s famous 4 valve cylinder heads, capable of propelling any motorcycle to 100mph.

|

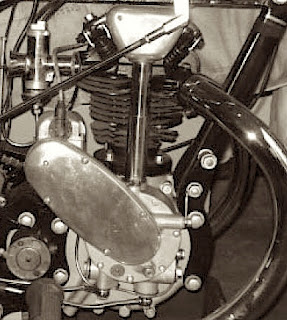

| A Rudge 'Python' 500cc engine, as sold to numerous small manufacturers in England and Europe; superior in performance and reliability to the usual JAP engine... |

O.E.C. (OsborneEngineering Co.) of Gosport (in Hampshire, England) were one such small company, always on the lookout for something new. Their best days followed WW1 when they built bikes exclusively for Blackburne in a large former aircraft factory. After Blackburne cancelled their exclusivity deal, O.E.C. embarked a series of seemingly brilliant associations, most of which came to nought. Their technical director, Fred Wood, was a man bursting with ideas, and had designed the impressive ‘Duplex’ frame before leaving an indelible impression on the motorcycling fraternity with his 1926 ‘Duplex’ steering system, using a unique set of parallel links for steering stability and suspension. A couple of years later Fred added a swinging-fork rear suspension system, controlled by spring boxes and a damping link. The Duplex steering system got a serious publicity boost at Olympia in 1930 when O.E.C. displayed their World Record breaker, built by Claude Temple and ridden by Joe Wright at 137.32mph at Arpajon, France, just outside the Montlhéry race circuit. [Of course O.E.C. also claimed a later recordactually taken by Wright’s Zenith, which you can read about here]

the Depression badly wounded O.E.C, and production costs needed to be cut. During 1932, Wood designed a new welded-up Duplex frame; the only lugs remaining controlled the swinging fork damping system and, on the girder-forked machines, the steering head. These welded frames were light and considerably cheaper to manufacture than traditional lugged frames…but would a conservative public accept such advanced thinking? All O.E.C. needed was an engine with sufficient urge to prove the new frames' potential. Enter the Rudge ‘Python’.

|

| Arthur Simcock on his 1933 Senior TT O.E.C-Rudge; note Webb girder forks and Duplex rear suspension |

After some years’ absence, O.E.C. entered 4 machines in the 1933 TT: two 250s and two 500s. All were Python-powered, and both Senior and Lightweight machines used one each of the Duplex steering and Webb girder forks. The frames were identical save for the power units and brake diameter. O.E.C. appointed ex-Sunbeam works rider Arthur “Digger” Simcock their team leader. The first machines built were the Webb-forked pair on which Simcock practiced, and subsequently rode in the TT. The Duplex machines were assembled at the TT by the second rider Alf Brewin and an assistant - no Ferrari budget here – and with little in the way of preparation, its not surprising that all the O.E.C's retired. Brewin did race them on the Continent after the TT but without success. This was typical of O.E.C's modus operandii - great ideas but poor organization.

Seven years ago I acquired a brace of OECs; one a race frame with Webb forks, the other a road bike with Druid forks, housing a genuine Blackburne racing engine. Years of research finally revealed that in 1936, the Australian O.E.C. dealer had acquired a racing machine with a Blackburne engine to promote the brand. Naturally, I wanted to re-unite the racing frame with its original engine, but this left a ruddy great hole in the “restored” frame. I decided Simcock's ‘lost’ Lightweight TT bike would be the inspiration, but no photos of it exist; I do have photos of his almost-identical Senior mount, so that became the template. The 1933 O.E.C. catalogue offers a J.A.P-engined, Druid-forked bike for £37/15-, and for an extra £7, you could buy Rudge or Blackburne power. This was the only year OEC offered ‘Python’ engines in this frame, for OEC fell into receivership later that year and Matchless engines were used thereafter. A 250 Rudge radial engine was what I really wanted but I couldn't find one in Australia. They are as rare as an ethical media baron here. In the absence of a Rudge engine, I briefly toyed with a J.A.P engine but my brain fade only lasted a few weeks. Five years ago the Australian Dollar was low against Sterling but it started climbing and eventually I was able to acquire a 1932 engine from the UK without having to mortgage the kids.

The biggest problem was the gearbox. I could not find a Rudge 250 box anywhere and so

reluctantly used the original Albion one. Interestingly, Dunelt's 1933 Lightweight TT bike combines a Python engine with an Albion gearbox, so a protocol existed. It took only three tries to successfully marry the engine and gearbox with the frame, thanks to laser cutting. The gear change mechanism required several cups of tea to sort, because unless you are Toulouse Lautrec or a contortionist, the original is far too high for aging hippies. Although O.E.C./Rudge 'TT Replica' engines did not have bronze heads, the exposed radial-valve arrangement is Rudge's signature and deserves pride of place. Heat resistant gold paint applied to the head and new laser-cut stainless rocker side plates should help drag people's eyes from the awful Ariel-green rear wheel.

As it turned out, the hardest part was the easiest. The exhaust pipes really are impressive. We are lucky to have a master in the otherwise lost art of exhaust pipe bending. Exhaust pipes should have an ever changing radius which, to achieve without flat spots, is a precious art form. John d'Arrietta uses the traditional method of packing the pipes with sand and skilfully applies heat in exactly the right places with exactly the right temperature before bending. The pipes hug the frame and primary cover where they should and are mirror images of each other. To my knowledge (and I have spent countless hours googling O.E.C, Python, Rudge, etc), it is the only OEC-Python 250 in existence and while not an exact clone of Simcock's historic machine, save for the hidden magneto pulley arrangement, all parts are correct for the period. It's on its way to northern France and the new owner intends to use it. It will soon be seen at historic events in England and the Continent.

Special thanks to Greg Rowse (splines and precision machining) and John Harris (welding), and Mervyn Stratford for advice on timing."

3:00 AM

3:00 AM

Posted in:

Posted in: